Gore Vidal, one of America’s greatest literary renaissance men and the master of the acerbic witticism, once said to an interviewer near the end of his life, “Anyone stupid enough to worry about how he will be remembered, deserves to be forgotten.” With Jay Parini’s new biography of Vidal earning high praise, and the recent documentary on Vidal’s bitter feud with right wing dean of letters, William F. Buckley, Jr., still attracting attention, many critics and commentators are considering the question of Gore Vidal’s legacy. Those who take the fate of American democracy seriously should use the abundant and abrasive opportunity of Vidal’s literature to inspect the danger of the country falling into every steel claw trap Vidal warned of existing on the ruinous road to empire.

An examination of Vidal’s art and politics is insufficient if it does not acknowledge the secular prophecy pulsating throughout the best of his novels and essays. It is not enough to merely enumerate the ideas Vidal helped introduce to American culture, or telegraph the time jumping bravery and brilliance of Vidal’s innovative artistry, but that is a good place to begin.

In 1948, Vidal wrote the first American novel to depict a same-sex love affair without any pathology or condemnation. “The City and The Pillar,” inspired by his own early affair with a classmate at his boarding school, ages well as a romantic story of youthful affection, simultaneously full of ecstasy and terror. For his trouble, shortly after the book’s publication, the New York Times announced on the pages of its books section that it would no longer lower itself to mention, much less review, another Vidal novel. Given that the New York Times set the standards for American journalism and cultural commentary during that decade, nearly every other major newspaper and magazine marched along with the boycott. Until the Times lifted the ban, Vidal wrote a series of mystery novels under a nom de plum, and moved to Hollywood, where he authored several screenplays for film and television, including “Ben-Hur.”

The American author soon became a public intellectual of such gravitas and grace that a Canadian academic would eventually devote an entire book to analyzing how he engineers a connection between entertainment and erudition in a televisual era of superficiality. “How To Be an Intellectual in the Age of TV: The Lessons of Gore Vidal” by Marcie Frank delineates a subtle style of engagement with the camera that seems alien to contemporary cable news, but helped propel Vidal to triumphant heights. He would risk it all again with the publication of “Myra Breckinridge,” a 1968 novel about a beautiful woman of bewitching power who slowly reveals herself as transgender.

The forward thinking and openness of Vidal’s early embrace and expression of sexuality stands in stark contrast to the dueling Puritanisms of the present age, where right wing moralists castigate sex in religious language, and left wing moralists prefer to warn of the dangers of sex in therapeutic terminology. Vidal considered himself a man not so much of the left, but of antiquity. Claiming inspiration from Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome, and writing one of his best novels, “Julian,” about the apostate emperor who tried to remove Christianity from Rome and restore paganism, Vidal personified the hedonism in existence before the influence of monotheism, and an unwavering loyalty to the early Athenian conception of representative democracy.

The cosmopolitan classicism of Vidal injected his contribution to political and literary culture with wisdom. The wisdom creates an unbreachable divide between Vidal, and for example, William F. Buckley. “Best of Enemies,” the recent documentary on their feud, treats them as equals. In reality, the record shows that unlike Vidal’s fine wine political positioning, Buckley’s retrograde views suffer decay and infirmity with each passing year. He opposed the civil rights movement, the women’s liberation movement, and the gay rights movement, and he celebrated Joseph McCarthy, supply side economics, and the war in Vietnam.

The connection pundits continue to trace between Vidal and Buckley, which precedes even the release of the documentary, is a small but significant illustration that America is either incapable or unwilling to learn from history (including its own), its past sins and errors or perspectives alternative to American exceptionalism.

One of the lessons Vidal would use his rhetorical ability and agility to amplify was the historical warning of Ancient Rome: “A nation cannot be a republic and an empire at the same time.” The respect Vidal showcased for America’s founding fathers emanates from the same point of caution. George Washington advised the nation against “foreign entanglements,” and John Adams considered “unnecessary war” society’s “greatest guilt.”

Vidal’s most ambitious literary venture was to retell American history while making it palatable for an American public with declining rates of literacy and interest in literature, by keeping focus on his country’s disastrous transformation from republic to empire. “Narratives of Empire” is a series of historical novels Vidal wrote to take readers from the early days of America’s independence all the way to the Truman administration, and the creation of the National Security State. An increasingly bloated bureaucracy – the Pentagon – gains more power as America repeats the errors of its imperial predecessors, extending itself further and further into every planetary corner while causing collapse within. President Eisenhower’s farewell address articulating the dangers of the “military-industrial complex” would prove too little too late, as America would soon start spending over half of discretionary dollars on the military, maintain over 800 military bases on foreign soil, and discard trillions of dollars and thousands of lives on largely pointless wars in Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

The bloodshed, limbs lost, and fortunes burned on imperial ambitions and foreign adventures compile hideous evidence validating the worst fears of the founders. Vidal’s novels map the treacherous path America took to lose its “golden age” – what Vidal calls the period immediately following World War II, when America was at peace for five years, the middle class was strong and stable and the arts flourished in cities from coast to coast – and the state of “perpetual war for perpetual peace” in which America is forever committed to vanquishing phantom threats belonging to the “enemy of the month club,” to use some of Vidal’s phrases from his essays.

The diversity and quality of Vidal’s essays earn him classification as one of America’s best purveyors of the medium. Reading his correspondences from his home in Italy on subjects ranging from sexuality to American history often feels like one has discovered a treasure chest full of letters from a wise and witty friend. Essays like “The Day The American Empire Ran Out of Gas,” “The National Security State” and “How We Missed the Saturday Dance” aggressively condemn a nation fast losing its bearings. Vidal had little patience for party partisanship or excuse-making for the right-ward drift of the Democratic Party. Republicans, of course, face even greater demolition at the hands of Vidal’s pen. “Armageddon?” and “Monotheism and Its Discontents” eviscerate the influence of religion on American politics and culture with more grace and nuance than Richard Dawkins could dream, and blunt force equal to the late Christopher Hitchens.

Twice Vidal attempted to battle the rise of despotic government and the degradation of political culture from the inside – running for Congress in New York, and the Senate in California. Long after he lost both races, he concluded that those defeats might have served him better than had he won: “A writer’s job is to tell the truth. A politician’s job is to not give the game away.”

Vidal once said that as a writer he chose to “make America his subject.” “I didn’t spend my life writing about the summer I lost tenure in Ann Arbor, because I ran off with the au pair girl,” he continued with characteristic sarcasm. His obsession with the early conception of America as a Republic with “only interests,” as Washington put it, earned him friends on the left – Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Susan Sontag – and the paleoconservative right – Pat Buchanan, Bill Kauffman.

Vidal was fond of quoting Benjamin Franklin, who after the passage of the United States Constitution remarked “A republic; if you can keep it.” It is easy to criticize the military-industrial complex, self-serving politicians, religious bullies, and mediocre journalists more adept at propaganda than reportage, but Vidal showed true courage and despair when he wrote with the realization that the people are part of the problem. Unlike Chomsky and Zinn, and more like Buchanan and Kauffman, he lost confidence that the American people were just enough information away from wrestling the country out of the arms of the elite and reclaiming the Republic.

In one of his final essays from 2006, Vidal wrote that America had “entered the Dark Ages.” “What we are seeing,” he explained, “are the obvious characteristics of the West after the fall of Rome: the triumph of religion over reason; the atrophy of education and critical thinking; the integration of religion, the state, and the apparatus of torture—a troika that was for Voltaire the central horror of the pre-Enlightenment world; as well as, today, the political and economic marginalization of our culture.”

None of the horror is possible without, at least, the tacit approval of a large percentage of the American public. Polls reveal that Americans are comfortable with drone killing and torture, that they do not believe in evolutionary biology, and that they no longer read much. Vidal once quipped, “Half of the American people read a newspaper. Half of the American people vote. Let us hope it is the same half.”

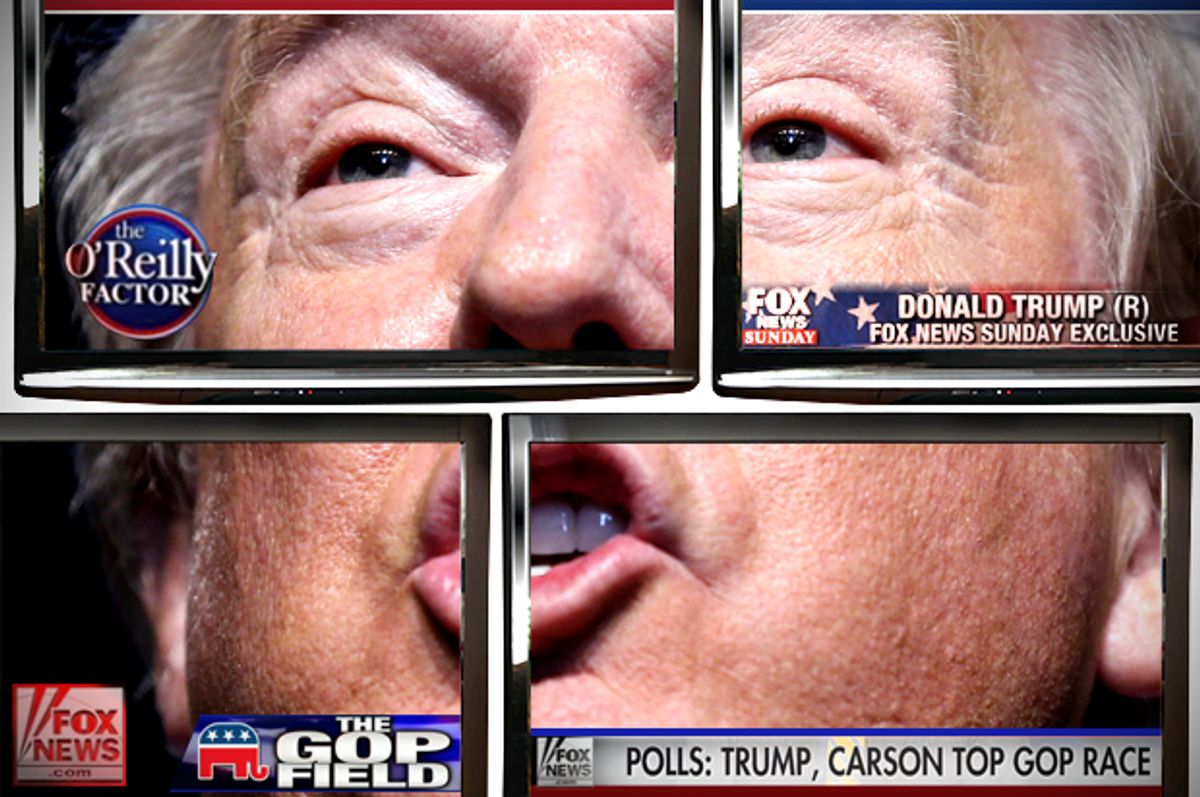

According to a recent Pew report, the percentage of Americans who claim to regularly read the newspaper – in print or online form – has now fallen to 29 percent. Only a fool would believe that the early success of Donald Trump, the sensationalism of cable news, and the celebration of ignorance that defines much of political debate are developments coincidental with the lack of curiosity and knowledge of the American people. Vidal was no fool, and his greatest fear near the end of his life seemed to be that the levers of power to pull for change were no longer accessible. It was the public – not so much the leadership – that was responsible for their destruction.

Any examination of Vidal’s life must take into account his role as not just critic, but in language he would appreciate, a more modern Paul Revere. Only in Vidal’s art and letters, he was not crying out for Americans to look out their window at the British, but rather to look in the mirror at the invasion they have already allowed.

Jay Parini’s new biography of Vidal, although well-written and fascinating in its chronicle of Vidal’s colorful life, does not spend much time on Vidal’s Revere-like role and his alienation from the American public. The title, however, gives an important insight through contrast. “Empire of Self” could refer to Vidal’s mountainous ego, but it could also refer to the self-earned elegance belonging to people who take the time and invest the effort and energy to truly discover themselves. Rather than allowing himself to be subsumed by the empire of mass culture – political propaganda, religious dogma, low-brow entertainment – he created an “empire of self” through political independence, free thought, and literature.

Ralph Waldo Emerson – another American original – wrote that in our society, “The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion.” The self-reliance of Vidal personified the romantic, American notion of individuality. Oddly enough, it is that form of individuality that is in such rare practice now, as it was when Emerson wrote his timeless essay on the subject.

In his progressive views on sexuality, his condemnation of American foreign policy, and his criticism of American voters, Vidal constructed an “empire of self” through the hard work of rebellion – a rebellion that provides a prototype for citizenship in a democratic culture. It is that exact rebellion America so desperately needs from its citizenry at this precise moment when too many Americans prefer to think of themselves as consumers rather than citizens. The almost artful irony is that Vidal’s work makes clear it is that rebellion which is least likely to occur.

Shares